Sir Clive Sinclair

Inventor, innovator, bon vivant

Sir Clive Sinclair passed away on 16 September 2021 after a long illness. This British computer pioneer, inventor and innovator brought affordable personal computers into our homes, influencing multiple generations of users, developers, and gaming enthusiasts.

Author: Michal Rybka

Sir Clive Sinclair and His Life - CONTENTS

- Sir Clive Sinclair Was a Computer Pioneer—and Much More

- Growing up in the Countryside Due to World War II

- Sinclair Was Ahead of His Time - Often to His Detriment

- Sinclair ZX80 (1980): The First Real Home Computer

- Sinclair ZX 81(1981) Sells Half a Million Units

- ZX Printer (1981): Thermal Printing at Its Most Extreme

- ZX Spectrum (1982) Makes History

- Sinclair QL: A Financial Disaster

- ZX Spectrum 128 (1985): Another Misstep

- Enter Electric Vehicles? Sinclair C5 (1985)

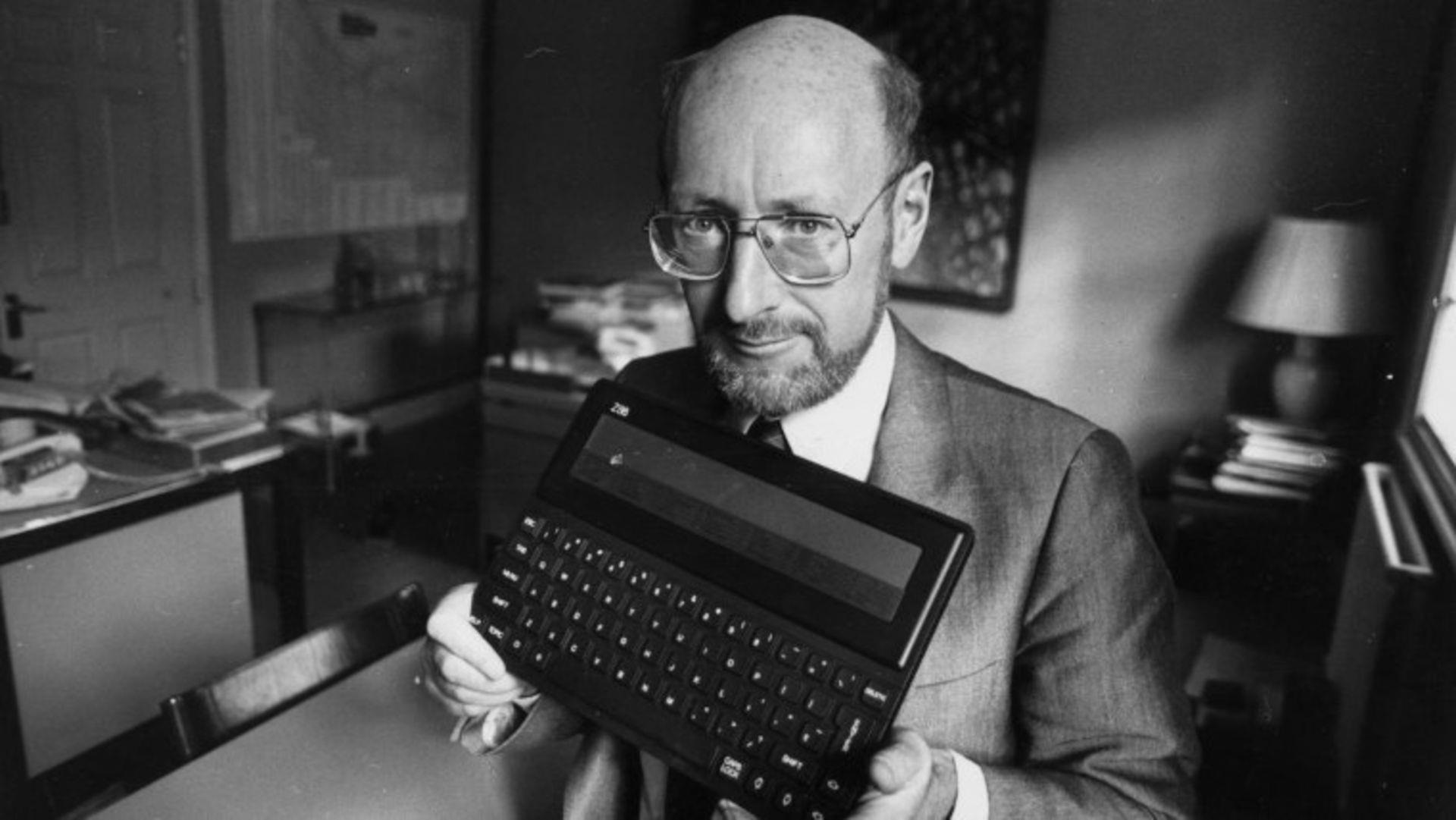

- Cambridge Z88: Clive Sinclair's Last Computer and the First Ultrabook

- A Submarine Scooter? 1990s Kept Sinclair Busy

- Recounting Sinclair's Personal Life Would Take an Entire Book

Sir Clive Sinclair Was a Computer Pioneer—and Much More

In Czech Republic, Clive Sinclair is best known for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum (1982) eight-bit computer—simply because it was probably the most popular eight-bit computer in the Communist Bloc in the 1980s. It was simple, powerful, and easy to copy, so in Czechoslovakia you could buy its Didaktik Gama and Didaktik M clones for Czechoslovakian crowns in normal retail stores, which was quite unusual. The countries of the former Soviet Union produced more than a hundred different clones of this computer model and it steadfastly remained the "first contact home computer" until the mid-1990s!

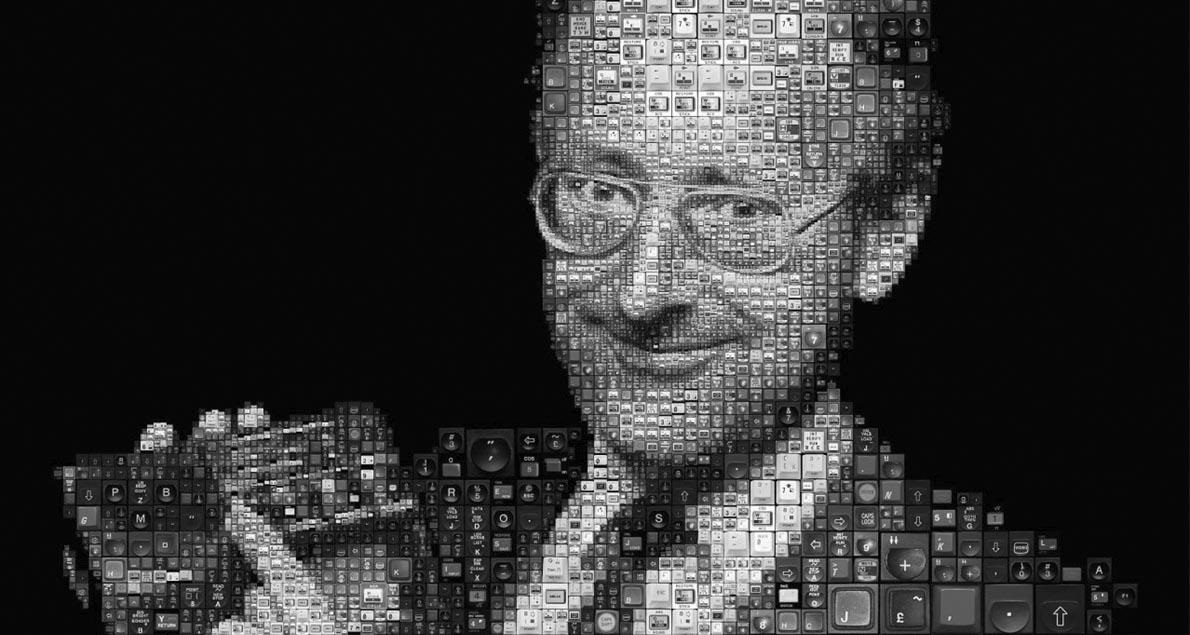

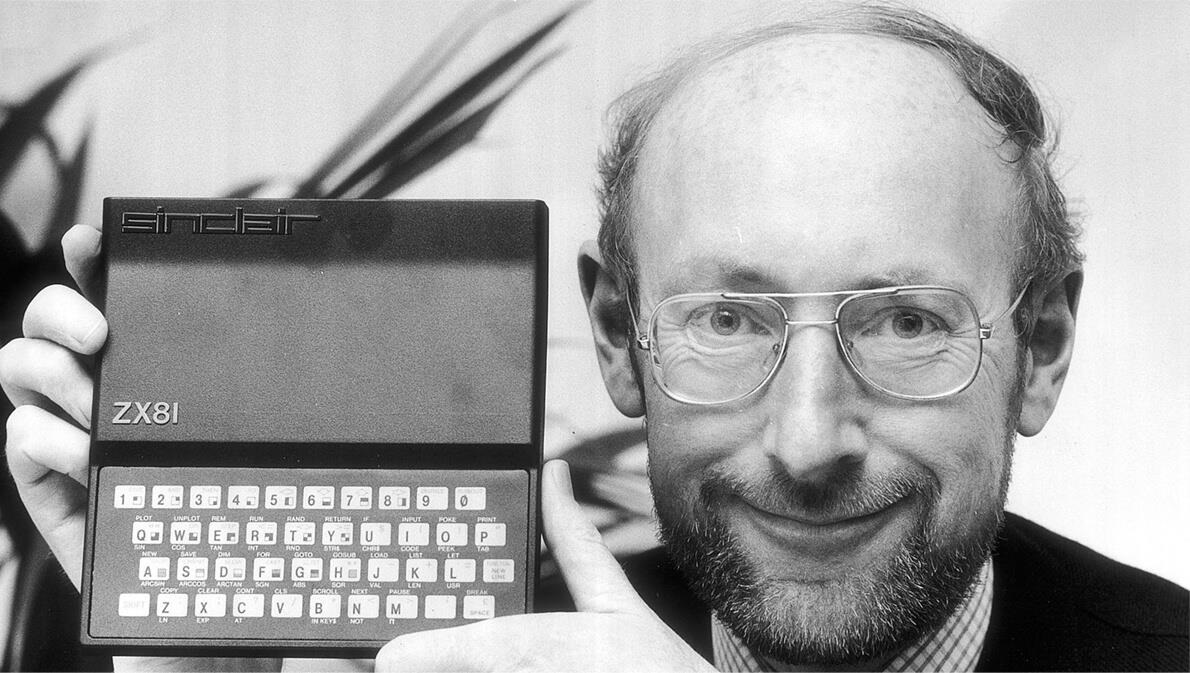

Sir Clive Sinclair and the legendary Sinclair ZX 81 from 1981.

The main reason was clear. Games. Despite the slightly exotic graphics architecture, the computer was very cheap and powerful for its time and offered colour graphics—and was easy to program for, resulting in a flood of newly developed games. It must be noted that Clive Sinclair himself was not exactly thrilled with the gaming success of his creation, as he intended it to be a tool for teaching computer literacy, not as a gaming machine to challenge the dominance of the Atari game console and the Commodore gaming computers in Europe.

Interview with Sir Clive Sinclair. It was broadcast in 1985.

Growing up in the Countryside Due to World War II

Clive Sinclair was born on 30 July 1940 when Europe was gripped by World War II. As a child he was evacuated to the countryside—and for a good reason, because their home in Richmond, Surrey, was hit by a German air raid. Sinclair's grandfather had developed a naval mine disposal device during World War I, so it seemed the boy was destined for a career as a military inventor.

Clive Sinclair's parents, and on the right Sir Sinclair himself in his youth.

Source: nostalgianerd.com

He did become an inventor, but in a very different way. Although he excelled in mathematics, he didn't enjoy school, didn't like sports, and didn't get along with his peers, preferring to keep company with adults from his own family. At fourteen he designed his own submarine and loved the holidays because the extra free time allowed him to study what he truly enjoyed. His dislike of school and his father's financial problems eventually led him to decide not to go to college, but to start earning money by experimenting with electronic building blocks he would order by mail.

Sample of Sinclair electronic kits.

Clive Sinclair had a passion for electronics since a young age and enjoyed it more than school. He worked as an editor for Practical Wireless magazine for a number of years and very soon began designing his own circuits. It was then that the arrival of the solid-state transistor revolutionised the field, so Sinclair began to explore how to build things in a simpler and less expensive way. This drive to make things small, cheap, and accessible remained his key motivation throughout his life and led to a number of innovations.

Sinclair Was Ahead of His Time—Often to His Detriment

In 1961, he founded Sinclair Radionics, a company that began manufacturing amplifiers and radio receivers. His Model Mark I radio kit, while not yet technically innovative, cost just 49p. The MAT 100 radio receiver was also smaller than a matchbox!

The 1970s saw the arrival of a range of new and exciting products—pocket calculators. His Sinclair Executive (1972) calculator still used extremely power-hungry light emitting diodes, but by optically magnifying the segments with an array of lenses and using a solution where the diodes only needed to 'flash' occasionally, it managed to extend battery life to a then unprecedented 20 hours.

Sinclair Executive Memory calculator from 1972.

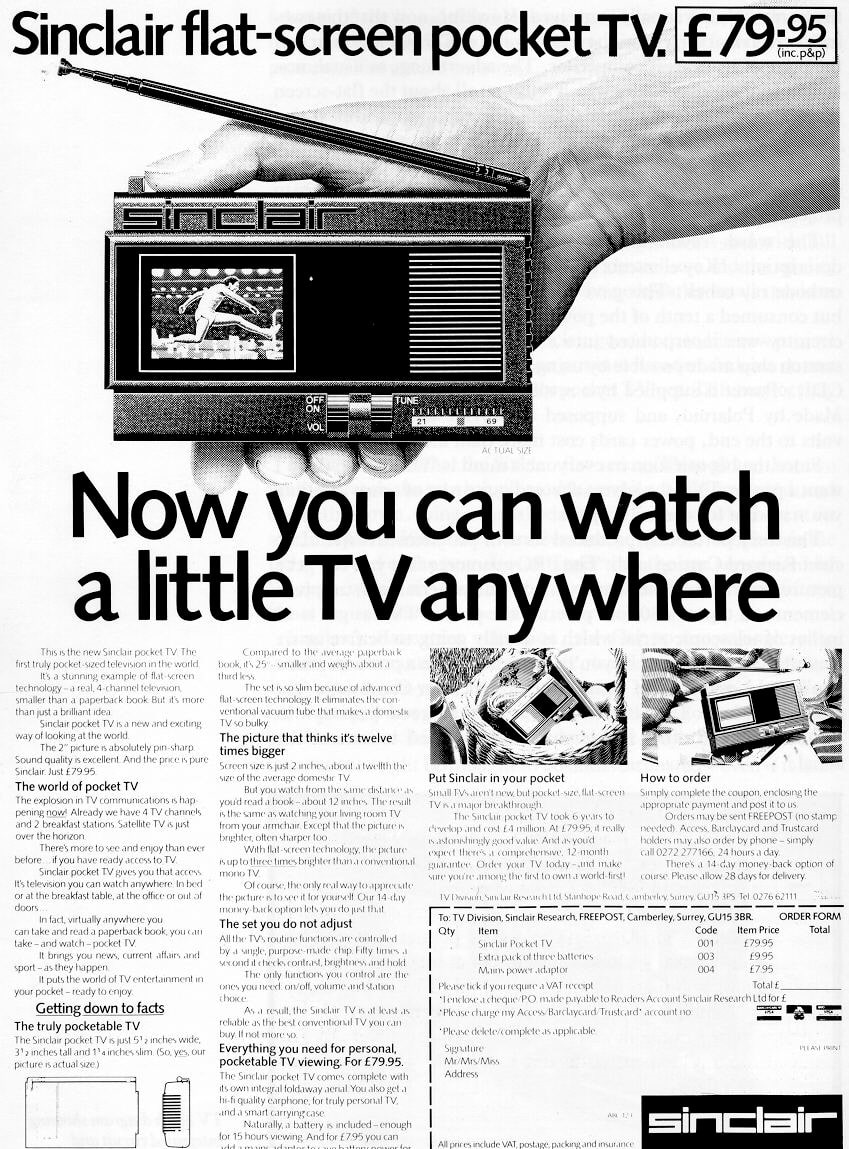

Even then, another feature of his products emerged - the pursuit of futuristic design. The Sinclair Executive is such an original design that it even made it into the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Similarly groundbreaking are his digital The Black Watch (1975) and the pocket television Sinclair TV80 (1983), which show a certain problem Sinclair had. He was somehow ahead of his time, going beyond what the market demanded, and he didn't hesitate to go for very innovative solutions, but which represented a technical compromise, because the technology just wasn't ripe for his ideas.

Sinclair The Black Watch Advert from 1975.

His devices were revolutionary and used novel solutions, but they simply came before the right components were even available. Low-power LCD displays were relatively rare at the time, so for his watches, Clive Sinclair used novel flashing LEDs. However, these LEDs were so power-intesive that the watch could only show you the time after a press of a button, and even this still meant that the watch battery only lasted only about 10 days. Another example was his compact TV80 pocket television. It arrived before flat panels became widely available, so it used a miniature screen magnified by a Fresnel lens.

TV news coverage of the Sinclair Flat Screen TV pocket television launch in 1983.

Clive Sinclair proved time and again that his ideas could circumvent the limits of current technology, but while they produced ground-breaking devices, these devices were far from user-friendly and had to incorporate many technical and design compromises. The Black Watch resulted in a financial loss, and the Sinclair TV80 sold only some 15,000 units—an outright flop compared to Casio's later LCD panel pocket TVs.

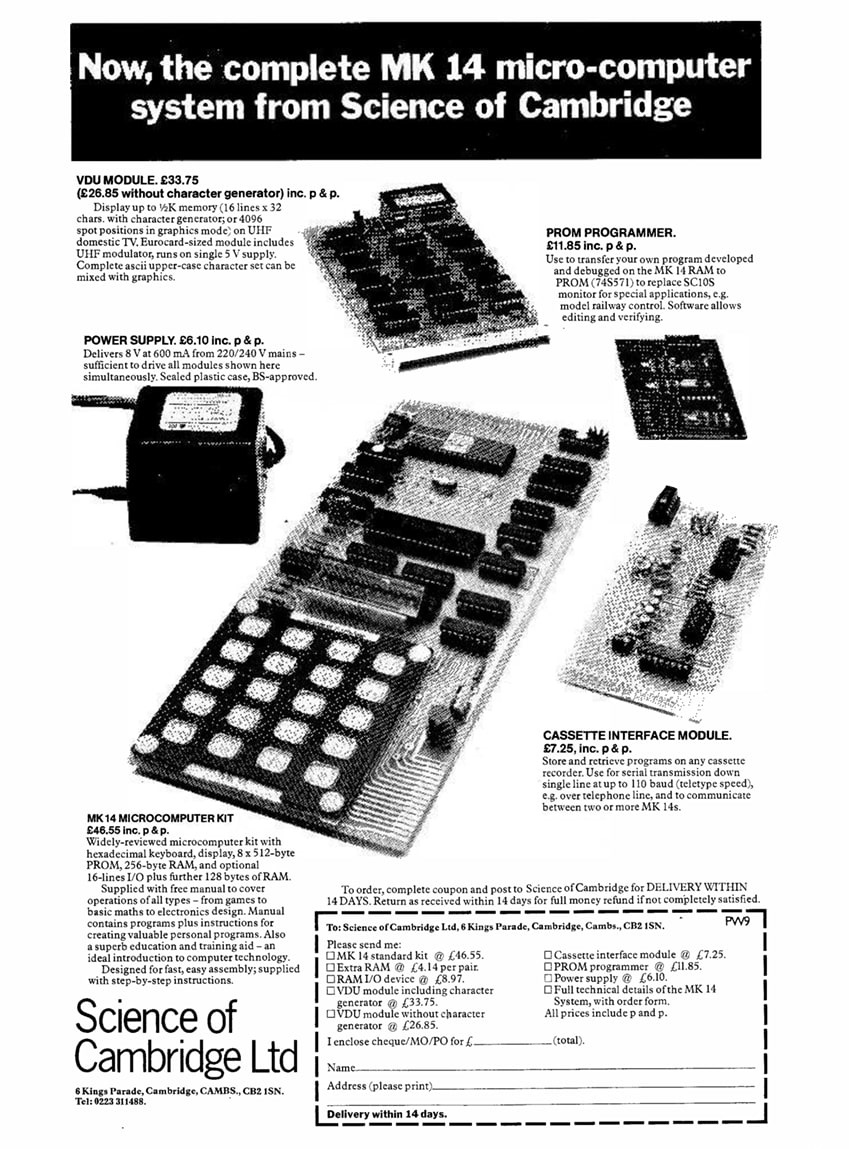

Due to financial problems and difficulties in finding investors, Clive Sinclair set up several companies in succession in order to move intellectual property between them. As a back-up, he established a company called Science of Cambridge, which began offering the Microcomputer Kit MK-14 (1977) building kit. This was a very simple computer with 256 bytes of RAM (640 bytes maximum on the board, with external expansion up to 2,170 bytes—actual bytes, not kilobytes!), 512 bytes of ROM, an eight-digit numeric display and a calculator keyboard. It was programmed directly in hexadecimal machine code, which made it a fun toy for engineers and not so much for ordinary users—but this primitive computer also boasted direct I/O connectors and an optional keyboard. Sinclair had to sell his own house to jump-start the production. It was a difficult, highly technical device, but it sold more than 15,000 units—and showed the potential for an affordable home computer.

Introducing the MK-14 computer kit.

Sinclair ZX80 (1980): The First Real Home Computer

The Sinclair ZX80 arrived in 1990 and it was the first real home computer—and a technical marvel given its price tag of under £100—£99.95 for the assembled version, £79.95 for the kit. A kit doesn't mean it was "built" like modern PCs, where you just plug in a couple of components and you are done. You got a circuit board, chips, some other components, and then you were left to your own devices and had to solder it all yourself, making building a PC a tad more complicated hobby than it is today. Clive Sinclair saw it as a teaching tool. Want to learn the art of home computing? Build your own!

This machine had a keyboard and a futuristic design, but it was still chock-full of technical compromises: 1kB RAM, membrane-only keyboard—nothing like today's membrane keyboards where you can't even see the membrane, though. Here, a membrane keyboard meant the keyboard itself was a membrane! The processor was also involved in generating the video signal, which took 80% of its capacity, so you briefly lost the picture every time the computer did something. To fit a BASIC program into memory, tokens were used: the user didn't type out commands, but each full command was a special character that had to be typed correctly on the keyboard. This machine was a modest success, selling about 50,000 units, but once again it had the typical Sinclair weirdness.

Alza Museum: The Sinclair ZX80, the first microcomputer for the masses.

Sinclair ZX 81(1981) Sells Half a Million Units

A year later came the first of the legendary computers: the Sinclair ZX 81 (1981). It was considerably simplified, with only four integrated circuits: processor, ROM, RAM and ULA—a custom circuit that replaced the 15 universal chips from the original ZX80. This drastically reduced the costs and simplified production—the fully assembled version had a price tag of £69.95 and the buildable kit only £49.95! The ZX 81 sold over half a million units and spawned a number of clones in the USA (Timex 1000), South America (Microdigital TK82, Czerweny CZ 1000) and Asia (Lambda 8300, Polybrain P118). Basically, all of them were the same machine with a few improvements: the flickering disappeared and the user could choose whether the computer would generate an image while running (slow mode) or turn off the display and let the processor run at full power (fast mode).

Alza Museum: The Boys from Brazil!

ZX Printer (1981): Thermal Printing at Its Most Extreme

Another typically atypical Sinclair invention was the ZX Printer (1981), which used a special aluminium-coated paper and worked by literally burning through the paper at high temperatures. This was probably the most extreme form of thermal printing, which still exists today after a fashion (you may know it from cash registers), though here it was all about maximum design simplicity without any regard to the printer's service life or the obstacles presented by its obviously exotic paper requirement. The printer had no intelligence of its own; the printing was fully operated by the computer.

ZX Spectrum (1982) Makes History

Clive Sinclair's most famous product is undoubtedly the ZX Spectrum (1982). This came in several versions, the most notable of which was the rubber keyboard version with a distinctive rainbow motif. The keyboard looked relatively "normal" as it covered the membrane, and the computer had 48kB of RAM, which meant it could hold a good number of programs. There were also rarer versions with 16kB of RAM and, conversely, the later ZX Spectrum Plus, which introduced a plastic keyboard instead of a rubber one, but the "rainbow" was simply a classic that brought colour computer imaging to the masses in the first half of the 1980s.

Alza Museum: ZX Spectrum, the legend.

At £174 it was an affordable computer and it established Sinclair as a real computer pioneer. It should be noted that even here, experimentation with non-standard features in the form of extension interfaces was in full swing: the ZX Interface 1 brought support for serial interfaces, as well as the non-standard ZX Net and the rather exotic ZX Microdrive, which was kind of like a floppy disk but with infinite tape—a revolutionary, inexpensive, yet somewhat insanely designed tape storage device.

The ZX Interface 2 brought two joystick ports, but it wasn't the standard Atari/Kempston sticks, but a unique Sinclair Joystick that emulated numeric key presses. Again, the core idea was good—any game that allowed you to define control keys automatically supported the Sinclair Joystick, but it was a non-standard device. Even more problematic was the ROM Port, which had a limited capacity and ROMs were expensive—they cost £15 each!—and so only 10 games were made in this format. The cassette recorder was king at the time, limited in reliability but much more affordable. Most Spectrum games were released via tape recorder and any gamer from that era probably remembers the infamous "R Tape loading error, 0:1" error message.

Introducing the Top 50 games that defined the ZX SPECTRUM.

Clive Sinclair continued with his typical missteps. He entered a competition for the official teaching computer for British education, but lost to Acorn. Ironically, Acorn envied Sinclair the popularity of his computers, but it was this company that managed to win the competition for the official BBC Micro. Sinclair, on the other hand, was upset that the ZX Spectrum had turned into a popular gaming machine because he had intended it to be a teaching instrument. This story was made into the 2009 film "Micro Men", which tells the story of the dramatic evolution of the computer market in the first half of the 1980s.

Trailer for Micro Men (2009).

Sinclair QL: A Financial Disaster

In 1984 came the Sinclair QL (Quantum Leap) machine, which was supposed to be Clive Sinclair's ticket into the semi-professional world, but instead it was a commercial catastrophe. It was a huge performance leap, where he went straight from the standard eight-bit Zilog Z80A processor to a thirty-two-bit Motorola 68008 processor—but with an eight-bit external data bus, which was quite a convoluted design choice. The computer was much more complex than expected and its operating system didn't fit into the planned ROM, so the first versions shipped with an external module. Rounding up all this trainwreck was the use of two Microdrive units, which were theoretically cheap but very problematic and, more importantly, incompatible with essentially anything the rest of the world was using.

Alza Museum: Sinclair QL, a revolutionary flop.

The result was expensive, hardware deficient, and totally incompatible. Sinclair expected to sell a million units in the first year, but actually sold only about 150,000 in total—and users had to expand and upgrade their computers to boot. In the end, the machine proved to be quite popular with those few who bought it, as it used progressive techniques like multitasking and had the Psion software pack that later gave rise to the popular handheld computers, but financially it was a flop. The upgraded ZX Spectrum Plus tended to overheat and the plastic keyboard had the unpleasant habit of chewing holes in the membrane, so the returns reached around 30%—at a time when the standard number was 5%. The PC and Amiga were also starting to gain ground at this time, presenting a very real problem for Sinclair's computers.

ZX Spectrum 128 (1985): Another Misstep

Sinclair roller-coastered from success to failure, creating the first version of the improved Spectrum—the Sinclair ZX Spectrum 128 (1985)—only to sell the brand to a British manufacturer Amstrad a year later. The Spectrum 128 brought a new mode with expanded memory and advanced music processing, but the original Spectrum was sort of brute-forced into it, so the computer had two modes and two BASICs with two different control methods. Again, it was equipped with a problem-prone keyboard, and to keep the computer at least somewhat cool, the power transistors had a prominent aluminium heat sink on the right, perfectly placed so you could burn your hand on it.

ZX Spectrum Vega: A retro console for Spectrum fans!

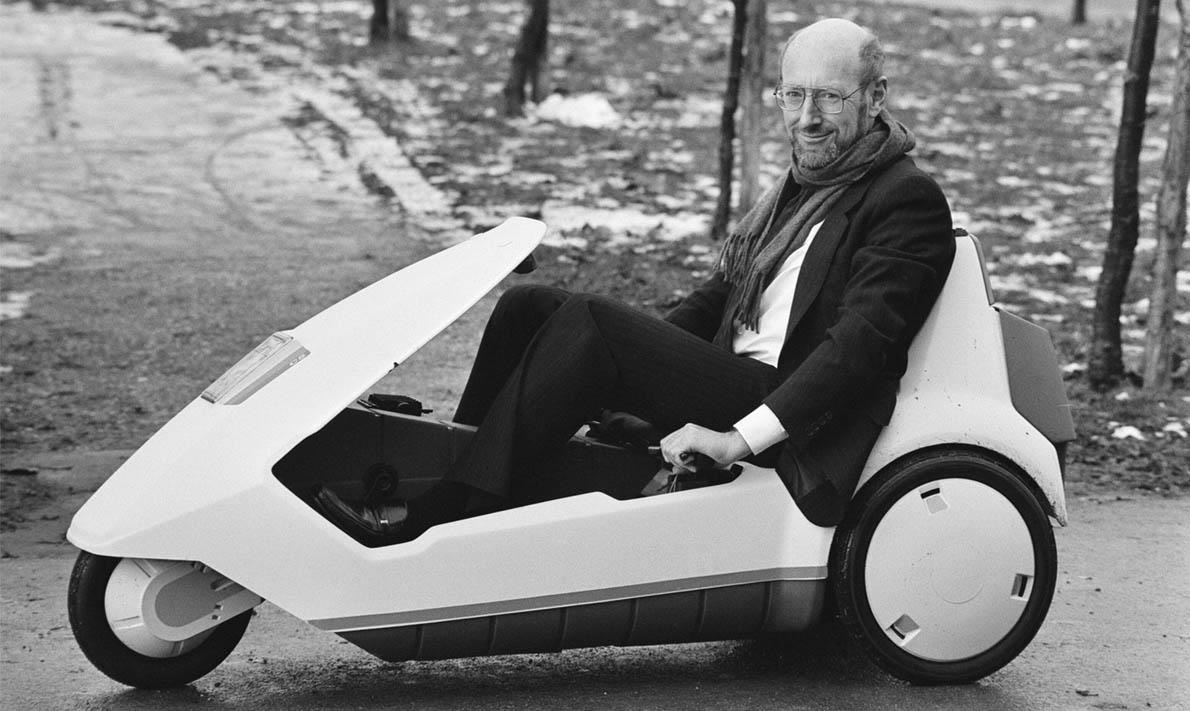

Enter Electric Vehicles? Sinclair C5 Electric Tricycle (1985)

This wasn't the only Sinclair fiasco, either. At the same time, Clive Sinclair also ventured into electric vehicles and designed the Sinclair C5 (1985) electric tricycle. It was a vision of futuristic electro-mobility, but it wasn't a car, it was a roofless tricycle that could be driven without a licence. As many times before, Sinclair's vision was ahead of its time. Unfortunately, it couldn't go very fast—the speed limit was 15 mph—nor very far, as its distance range was 20 miles (30 km) in ideal conditions. It couldn't climb uphill either, forcing you to pedal away, you could barely take any bags with you, and if the weather was bad, you had to wear a raincoat (purchased separately). You also had to pray it wasn't too cold, because then the battery couldn't generate enough power—or too hot for that matter, because it would overheat. Moreover, it was really dangerous in normal traffic, as the driver sat so low they could barely see the surrounding traffic and most importantly, it was difficult for other drivers to see this little contraption. The tricycle was ultimately so dangerous it got banned in the Netherlands!

A 1985 ad for the Sinclair C5.

Despite all the faults, 17,000 tricycles were sold, which ironically was enough to make it the best-selling electric vehicle until 2010, but even so the financial loss was around £7 million and Sinclair had no choice but to sell the Sinclair brand.

Amstrad, to whom Clive Sinclair had to sell his computer brand, simplified the design of the ZX Spectrum 128 and sold it in several versions: two versions with a cassette recorder (+2, +2A), a version with a non-standard 3" floppy drive (+3) and finally a home PC (Sinclair PC200), all under the Sinclair brand. In all cases, however, it was only milking the brand further rather and innovating. All versions of the ZX Spectrum sold a total of about 5 million units.

What made Sinclair's last computer so brilliant and how can it still be useful today? Watch the video to find out more.

Cambridge Z88: Clive Sinclair's Last Computer and the First Ultrabook

Clive Sinclair made one more computer under the Cambridge Computer brand. This was the innovative Cambridge Z88 (1988), which today, with its 0.9 kg weight, would be considered an ultrabook: it could run for 20 hours on four AA batteries, looked like an A4 sized board with a rubber keyboard and a 640 × 64-pixel unlit, noodle-shaped display, and allowed office work. The computer was expandable to up to 3.5 MB of RAM and stored data on EPROM modules, or what we would now call SSDs.

The Cambridge Z88 was Sinclair's last computer.

It was an extremely advanced machine, but as usual it was not compatible with anything, the screen could not be positioned and it was not backlit, so its practical usefulness was limited—classic Clive Sinclair. In the 1990s he returned to electro-mobility, designing the ultra-lightweight Zike electric bike (1992), which weighed only 11kg, could recuperate, but still only sold 2,000 units, supposedly because of the Sinclair C5's bad reputation.

A contemporary interview with Clive Sinclair at the launch of the Zike electric bike on Tomorrow's World.

A Submarine Scooter? 1990s Kept Sinclair Busy

He then turned his attention to accessories for classic bikes, namely the Zeta add-on motor, which came in three versions (the last, Zeta 3, was still being sold after 2000). In 2002 he turned the Zeta into the Wheelchair Drive Unit, an electric motor upgrade for wheelchairs—but it wouldn't be Sinclair if he were practical about it, so the result was not an electric wheelchair but an assistive device which wasn't designed to be controlled by the wheelchair's occupant. Clive Sinclair then went on to design the A-Bike (2006), a folding bicycle, and the Sea Scooter (2001), an "underwater scooter" the diver would hang on to and let himself or herself be pulled at speeds of up to 3 km/h for one hour. The A-Bike was later also offered in an electric version—and both it and the Sea Scooter turned out to be successful.

Sea Scooter ad.

Recounting Sinclair's Personal Life Would Take an Entire Book

Clive Sinclair's life was a roller coaster. He got rich and then bankrupt several times—and because he had a fondness for all things risky, he played poker, even winning the first series of Celebrity Poker Club. His love affairs were similar, resulting in his divorcing his first wife Ann Trevor-Briscoe in 1985—and it was the most expensive celebrity divorce of the time. He had a string of mistresses, managing to marry former beauty queen Angie Bowness, 36 years his junior, at the age of 70. Apparently it wasn't all about the money either, as Sinclair was known not only for his charisma but also his keen intelligence, having served as the head of British Mensa from 1980-1997 with a measured IQ of 159.

Clive Sinclair in the 1999 British television series Late Night Poker.

Although he was a computer pioneer, he refused to use computers or the Internet himself and was deeply sceptical of artificial intelligence, even claiming that the advent of artificial intelligence surpassing humans would make it "very difficult for us to survive". He was knighted in 1983, and despite the repeated failures, as late as 2010 he was still planning to create a new version of the Sinclair X1 electric vehicle that would solve the problems suffered by his C5 model.

Sinclair was an energetic and vivacious individual, leaving behind three children, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. He did a lot and tried a lot, though sometimes it led him to some dead ends. Although he was occasionally extremely successful, one can't help but feel that some of his success was a happy coincidence and that he didn't care much for how people actually used his products and what they really wanted. Sinclair innovated in his own way, bypassing the limits of his age and taking risks in search of revolutionary concepts. He may not have been the best technology entrepreneur, but he was certainly an extremely creative innovator and a great inventor of our time for whom nothing was impossible.

Michal Rybka

Michal Rybka je publicista a nadšenec s 20 rokmi skúseností v IT a gamingu. Je kurátorom AlzaMuzea a YouTube kanála AlzaTech. Napísal niekoľko fantasy a sci-fi poviedok, ktoré vyšli v knižnej podobe, a pravidelne pokrýva piatkový obsah na internetovom magazíne PCTuning.